John Grossman

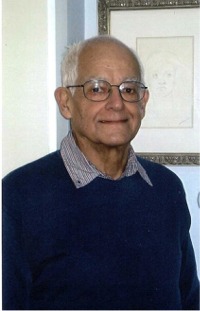

Name: John Grossman

Rank: T4

Date of Birth: October 1924

Birth Place: Cleveland, OH

War: WWII

Dates of Service: 1943 – 1946

Branch: US Army

Unit: 12th Armored Division

Location: Germany, England, France

Prisoner of War: No

Interview Transcript

Today is November 30, 2007. This is Fidencio Marbella with the Melrose Park Public Library. We’re here also with Heidi Krug also with the Melrose Park Public Library in Illinois. Today we’ll be speaking with Mr. John Grossman. John served in the United States Army from 1943 through 1946. He achieved the rank of T4. John is a current resident of Oak Park, Illinois. This interview is being conducted for the Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress. Okay, let’s go ahead and get started John.

All right.

Why don’t you tell me when and where you were born?

I was born in Cleveland, Ohio in October of 1924.

Tell us a little about your parents, their occupations and anything you want to tell us about any siblings you had.

I had one sibling, a sister who was three years older than I and my father was a physician and my mother was a housewife. That constituted our entire family.

Now, tell us a little about your early days in the service. You mentioned that you were drafted in 1943.

Yes.

Can you tell us where you were when you heard about the Pearl Harbor attack?

I was at home. It was on a Sunday and I was doing homework upstairs and I heard some sort of discussion, loud discussion between my mother and father, kind of surprised tone of voice so I went downstairs and over the radio they had announced that the attack had been made on Pearl Harbor and I believe they also mentioned some of the coordinated attacks on Wake Island or the Philippines or something like that too. And I knew that meant eventually I would be joining the service.

So you were in high school at the time?

High school. It was my junior year, I believe and I was deferred, of course, until my senior year was complete. I took a test; hold on, I’m jumping the gun here. I took a test in my senior year to see whether I qualified for the Army Specialized Training Program, or ASTP. The Navy had a similar program. V12 theirs was, ours was A12. To send the qualified military personnel to college for a degree in, it started out with basic engineering courses. And then we could from there go to pre-medicine, which is what I wanted desperately. I wanted very much to be a physician, or into Languages and Area that I think was connected with intelligence or occupation and so forth. I passed that test and so I took basic training in an ASTP unit in Camp Hood, North Camp Hood, Texas. That was a temporary camp built north of the permanent Fort Hood, just for this war. After basic training we were sent to various colleges. I was sent to a college in New Mexico, New Mexico Agricultural and Mining College, no Agricultural and Mechanical Arts, and was there for two semesters. I didn’t quite complete the second semester because the program was broken up in anticipation of the invasion of Europe. Up until that point they didn’t need so many of us. They were concentrated in North Africa. In the meantime, I had taken a test to see whether I qualified for transfer to medicine, the study of medicine, and I passed that test and I was kind of hoping that I would get there, but the invasion had other plans for me. From there I went to Camp Barkley in Texas to join the 12th Armored Division. Is it necessary to explain what an armored division was?

If you’d like to.

It’s a division whose main purpose is to make quick advances far into enemy territory through breaks in the stationary line. All the personnel in an armored division is transported by vehicle, whether it be by half track, which is what we used, the infantry used and I was a medic in the infantry, for an infantry battalion; or tanks, motorized artillery or reconnaissance. In other words, there were a variety of services within this one division and they were all motorized. There were more personnel in a regular infantry division. Ours was made for speed, quickness and unfortunately, the first two battles we were in were stationary battles, much to our displeasure and suffering, casualties. But after that when the allies entered Germany, then we became a real armored division and just sped through there very rapidly in advance of the other army units.

So they had to walk and you got to ride.

That’s right.

You did your training in Texas. Did you ship out directly from Texas or were there other places you had to do some more training at?

No that was it. We took trains. You know during the war they brought old trains out of Cosmoline or something and put them on the tracks and so we rode on these old trains all the way from Texas, north and through Cleveland, where I lived and we stopped. The train stopped in the yards, the railroad yards there for some reason. I don’t know, maybe for traffic and while we were stopped, the local population discovered us and came running to look at these soldiers who were on their way to war. One lady said, “Is there anybody from Cleveland on the train?” I said, “Yes, I’m from Cleveland!” And then she said she wanted to know the names of my parents and how she could get a hold of them so that she could say that she saw me. Now, I told her who my parents were. I gave her their telephone number and that was it. We began to move and I’ve often wondered whether I broke the code of silence, but I trusted her and believed that she would not spread the word to anyone but my parents. From there we went to Camp Shanks, which was in New Jersey, I believe, near New York City. Matter of fact, we were there a few days and I had a pass to New York City, a day, maybe for a couple of hours.

What was that like?

Oh, it was exciting to walk through New York with your uniform. Then we got on a British boat, something we used to call a tramp steamer, not one of those big freight boats, but a smaller version, which still had capacity for cargo. It took fourteen days in convoy to cross the Atlantic and we had no encounter with the enemy, although there were numerous Navy combat vessels that were with us. The food was British food; it was terrible, terrible, but we endured it and we landed in Liverpool, England and immediately, as soon as we got on trains in Liverpool some nice army people, British Army people came around with little breakfasts for us, packaged breakfasts, and those were rather tasty, so we were happy about that. And then we went by train to a place called Tidworth Barracks. This was a regular, army establishment, but we weren’t in any buildings, we were in square tents with wooden floors and coal-burning stoves in the middle and it was getting cold at that time, especially in England so we enjoyed the coal stoves.

Was this around 1944? Early ’44?

No, this was in the beginning of autumn, 1944, maybe September, something like that. We were there for one or two weeks and had passes to go to places like, Andover was one place we went and Salisbury and to London. In Salisbury they have a nice cathedral and if you look up under the spire you see that the stone structure bends and it has been like that for well over a couple of hundred years. It’s still standing where it was when I was there. One evening the London Symphony Orchestra played in that cathedral and I and some of my friends were able to go there on a pass. And when I had a pass to London I heard them again in their regular home.

Did you have much contact with the British people? What were they like?

They were, the ones I had contact with, a few, we were kind of restricted but I did encounter a few and they were very nice. We had heard that some were resentful of Yanks.

Overpaid, oversexed and over here?

That’s right, that’s right, but we didn’t consider ourselves overpaid or oversexed. So we got along. Then we got ready to ship over to Europe and we went into a convoy down to Southampton and got on LS, landing craft, troops.

LCTs? LCIs?

Yes, something like that. Ours was rather large and could accommodate a vehicle or two. We went across to Le Havre, that’s the French way of pronouncing it and we went through there on trucks and saw the damage that had been done during the invasion to Le Havre. Then we went across the river into Calvados territory and stopped at a small village called Aufay, A-U-F-A-Y. We stayed, the medics at least stayed in a small chateau. I don’t really think it deserved the name of chateau, but that’s what they called it. In the basement we found large bricks of compressed sauerkraut that the Germans had left behind and I was glad when I saw those that I wasn’t a member of the German Army. We were outside the chateau one night, one evening and some little boys, the village was up a hill, almost a cliff and there was a stairway up there and these boys were from the village. They came down out of curiosity to see the American soldiers. We had been issued little French phrase books in case we wanted to have some conversations. So I looked in the phrase book for these two boys. They were all very pleasant and happy. I said, I looked in there and found this phrase “avez-vous de pain?” which means I guess, “Have you any bread?” I don’t know, I didn’t really need any bread. I was fed plenty of bread by the army, but it was a phrase and one little boy said “Oui! Oui!” and then motioned that I should follow him and so we went up the stairs, up to the village and he took me to, and a couple of friends to his home and introduced me to his father and mother and two other adults who were visiting at the time and the boy spoke to his parents in French, who were very excited about it all, these American soldiers I guess. They said oh yes, oui oui and so the mother went to her kitchen and brought out some cider and some bread, some “pain” and so we had a little party there. We tried to express ourselves, but it was difficult because at that time I knew practically no French at all, but we had a very nice time, they were so lovely. The people were so lovely and then we left and went back to our chateau. Another time we decided to have dinner at one of the restaurants up there and have a little something to eat. Everybody was very nice.

So even during war it wasn’t that hard to find a nice French restaurant.

That’s right, that’s right. Well, I’m probably telling you more than you need to know. And then we were in that chateau; the whole division was in that area for some time. So we set up an aid station, well a dispensary. There was no action yet, but in case anybody went out sick, but fortunately nobody got sick. It was in one of the outbuildings of the chateau. Eventually it was time to move out. We went in a long motorcade, all of our various vehicles, halftracks and tanks, mobile artillery and ambulances and jeeps although in an armored division they were not called jeeps, they were called peeps. I don’t know why, we were told that but we hardly ever used the word peeps, we spoke of them as jeeps. This long column wound through Compiégne, Soissons, Reims and Verdun and then to the province of Lorraine. Most of our bad experience in combat was in Alsace and Lorraine, especially Alsace. We stopped at a town called Luneville and there was an old barracks, an old French Army barracks where we stayed for a few days and where we deposited our duffel bags which contained all of our extra clothing and in my case a medical book, an anatomy book that I borrowed from father because I still wanted to study medicine and we had to leave those behind and we went off. We knew that meant we were on our way to battle and so we just had the clothes we had on and we didn’t get much chance anyway in battle to change clothes, but if we did, we had khaki colored underwear so that if we had to undress down to our briefs, that part of us would be camouflaged. Still blend in. Our flesh would not be camouflaged. Anyway, so then we were in the combat zone. Our initial engagement was in Uttenweiler, just across the border into Germany from Alsace and I’m not sure why they wanted us to get Uttenweiler for them but we managed to. Uttenweiler was defended by what was called the Volkssturm. They had kind of run out of sufficient army personnel, so they had to induct older men and young boys and we saw some of these young boys and they were really young boys, but they were very enthusiastic as boys will be as I was when I was a boy. I thought war was glorious. The old men knew better but they had to do it, of course. Overcoming them was pretty easy. We set up our aid station in an old farmhouse and then our captain, a doctor, wanted to, we had two medical officers, a captain and a first lieutenant, and there was also a dentist with us too. He did actually do work on some boys when we were out of the line in a rest area. He had a, this is a digression, but he had a drill set up but it had to be operated by pressing a pedal, so he had an assistant who pressed the pedal while he did the drilling.

Was that like an old sewing machine?

Yeah, it’s exactly what it was. Fortunately, I never had to have that done.

So this would have been in late 1944?

Yes, yes. We reached Europe, from England in, well it may have already been November or close to November.

By then, were a lot of your fellow soldiers thinking the war was almost over?

No. We were not, we did not think that. All we really did was just concentrate on the present and try to do our job and stay alive. So our infantry companies advanced against this town which was Uttenweiler in Germany and they took it and the Volkssturm, they retreated to hills beyond the city. We were, the city, village, was separated from our forward aid station by another hill and another medic and I, when we had finished setting up our forward aid station in a kind of a draw, surrounded on one side by shrubbery, we grabbed a stretcher, a litter, and ran up the hill looking for wounded Americans. We found a couple on the way up who were sitting on the side of the hill, but they were minor wounds so we bandaged them and told them to go back to the rear aid station. Later on when we got to the top of the hill, we found a dead soldier and we turned him over and his stomach was blown up. He had blown himself up on his own, he was creeping along the ground and he had placed one of his grenades in the wrong place and the pin, the ring had got caught on a weed or something, shrubbery or a stick and it came out and he didn’t know it. He turned out to be somebody who had been in Army Specialized Training with me, so it was a terrible shock, a terrible shock. Larisch and me filled out the form that we had to fill out for the soldier. We put his rifle bayonet first into the ground and his helmet on top so that graves registration would know to pick him up. And then we were on our way down when suddenly a barrage started landing on the hill, a barrage from the Volkssturm who had retreated to another hill and were lobbing mortar shells. So Larisch and I, the best place we could find for cover were the impressions that a tank tread had made in the kind of soft mud. The impression was maybe two inches deep, but we laid there anyway because that was the best support, the best defense we could find and the shells were dropping all around us. Then suddenly, this second lieutenant appeared standing above us. He was standing in all of this barrage and he had a strange smile on his face. I’ll never forget it. He looked down at us kind of as though he was amused by our trying to conceal ourselves, well perhaps in a two-inch depression, yes. But then eventually the barrage stopped, or paused and he went his way and we went our way and we couldn’t find any more wounded, fortunately, so we went down to the bottom of the hill where our captain was standing along with a couple of other medics. Then the medics who were still up on the hill brought down one wounded soldier and we treated him at the base of the hill and then they came down with another soldier on the stretcher and we could see immediately that this was an officer, a second lieutenant. And it was the second lieutenant who was standing over us, and to see him lying there with a gray face and his jaw, relaxed jaw and his half open eyes was a terrible, terrible thing. I don’t know what happened whether, I had the feeling he was courting death, I really did but I hope I’m wrong. But anyway, he didn’t make it. Then a little more action took place and finally we were, our troops were totally successful in capturing this town and getting rid of the Volkssturm. We were there for a few more days, through Christmas as a matter of fact and so celebrated Christmas there and there was no more trouble except there was a rumor, which was supposed to have proved true that some Germans were wearing American uniforms had infiltrated and actually captured sleeping American soldiers in some barn and made them come with them, one of whom didn’t have any shoes. He wanted to put on his shoes, but they wouldn’t let him so he walked through the snow and they were prisoners for the rest of the war. But we never saw these Germans. We were told to be on the lookout for them but they never came back.

How would you have been able to tell if you did run across them?

I know, it would have been too, unless you started to talk with them, but they spoke, they were said to have spoken English very well so I don’t know how we would have told. I’m glad we didn’t have to give it a try. But then we celebrated; the kitchen trucks came up on Christmas Day and gave us a chicken dinner. It was really very nice with mashed potatoes and everything. It was hard to believe that we had this while we were in combat, but then a day or two after that we were withdrawn and replaced by a regular infantry outfit. That was the end of our first engagement, which was bad, but not terrible. It was something that the infantry achieved with little trouble, problems and we medics did our jobs too. So we were at rest for a while in a sort of rear area, several miles behind the lines and that was when our dentist set up his drilling machine and tortured some of the soldiers. Then we were notified that we had to get ready for another action and this was said to be another case where the infiltrators, an army had crossed the Rhine River into Alsace in little boats and it too was composed of the Volkssturm, but that turned out to be a terrible error because instead of the Volkssturm, there was an SS unit and there were elements of several German infantry regiments and there were tanks and field artillery, so we were terribly misled and we thought this would be another easy job but it turned out to be a dreadful, dreadful experience, especially for the men on the line, the soldiers and the medics who were accompanying them. That’s something perhaps I should mention. Two of our medics were assigned to each of the companies of our regiment and they couldn’t stay at the aid station as we did. Larisch and I were, served that way when we went up the hill but then I was sent back. I was promoted to a T4 so I was in the aid station. They were company aid men; there were two per company. When the first attack was made against the town, I better go back, the name of one of these towns that was our goal was called Herrlisheim. Alsace, Alsace itself and part of Lorraine were throughout history sort of switched back and forth between Germany and France. Before the War of 1870 it belonged to Germany, belonged to France and the outcome of the War of 1870 was a victory for Germany and so it became German and then at the end of WWI, it became French again. So a lot of, many of the towns there have German names and many of the people who live there are native German people. Herrlisheim was the objective, one of the main objectives of our combat command. The name of the German offensive into Alsace was called Nordwind, which is German for Northwind and there were two prongs. There were two prongs from the north and one that came across the Rhine. And they were, this was at near the very end of the Battle of the Bulge, the Germans were being defeated and pushed back and so Von Runstedt, who was one of the leaders of the Bulge was pulled out of there and told to go down south into Alsace to see what we could do down there. So he took a pretty strong force and came down into Alsace and that was the Volkssturm that we were supposed to encounter there. So I was in the Seventh Army, our division was in the Seventh Army and because of the bulge many of our divisions in the army were stretched out to replace the Third Army, Patton’s Third Army which had gone up to break into the Bulge, which they did, so our line was rather thin there, so they thought it would be a good place to break through and form a second bulge.

Now at the time that this was going on were you aware of all these major counter attacks, or were you just concerned with your own little corner of Europe?

Yes we were concerned with our own little corner, we were pretty ignorant of what was going on in all other parts of the fronts, it was pretty isolated and we had our own concerns and somehow that was enough for us. But I would like to read something if I may about fear in combat because it’s something I felt very strongly. Although it was impossible to enter the minds or experience the emotions of my comrades or of other soldiers far a field I was nevertheless, by signs and dialogs and by the measure of my own feelings fairly well convinced that virtually all soldiers who are in combat live with fear. The great courage shown by some, the puzzling indifference displayed by others and even what appears to be the courting of death by a few all have in common despite such differences a very deep seated fear and awe of death as well as of injury causing unbearable pain and future disfigurement. Before the invention and widespread use of modern killing devices there was a better chance that a soldier would survive a battle and that there would be some glory with which to treat oneself at the end. During the American Civil War and especially during the War of 1914 and 1918 the numbers of killed wounded and maimed rose to grotesque heights and going to battle ultimately involved, by one method or another, the management or overcoming of great fear and in many cases the imagination or apprehension of receiving a mortal wound or a painful wound or a disabling wound. In the Second World War as well as the in the First, some soldiers were possessed by greater fear than others or perhaps were less able to manage or overcome that fear. For a few, battle was actually thrilling. Though it may always have been the hazard and the fear underlying or hidden within that attitude that made it so. I was not one of those few. For the vast majority I think, fear was a close companion that left us rarely and only for short periods of time. I count myself among that majority. Though often when I looked at the others at their faces and listened to their talk, I suspected that I bore a greater share of fear than they, that I was perhaps more aware of the proximity of danger and the nearness of death, or that I imagined it more vividly and more unrelentingly than they or that I lacked their ability to subjugate fear to their sense of unity and fellowship in the common cause or to the cause itself. Perhaps some of them looking at me felt the same way for nothing in my face I feel sure betrayed my deep and unrelenting inner struggle. What kept us going of course was the knowledge that what we were doing had to be done and that the alternative was too horrible to contemplate. For us, therefore, there was no way out. No way that is except through injury or death. And so we kept on doing our jobs in spite of fear even if that fear sometimes grew to terror. I am making speeches.

That said an awful lot.

Our position, I already spoke about Volkssturm, though I have to read this other thing. This I call “The Stress of Caring for the Wounded.” It was time when we were in fighting for Herrlisheim, when our infantry was fighting. It was time to get back into the war after our brief rest. To hear again the thunderous explosions, to see again the fiery eruptions and the billowing smoke, to hear once more the staccato racket of machine guns and the crack crack crack of rifle and small arms fire and to encounter the terrible transformation of living, moving men into the slack-jawed inert dead. It was time once again to attend the wounded. The screams of them in their terrible pain, staunch their copious bleeding all the while considering the possibility of suffering a similar fate oneself. The variety and yet somehow the awful similarity of the wounded required the quickest attention and the sudden understanding of how best to help them. Though sometimes there were so many all at once that it was difficult to know which of them to tend to first. One always felt their utter and terrible dependency on how and when we treated them and there was always the concern that one might do the wrong thing too fast or the right thing too slow.

Being a medic, are there any men or situations or incidents that stand out more than others? That you remember, aside from the lieutenant that stood over you?

Yes there was, I told you already about the friend of mine who we found on the hill with the grenade, he had blown himself up with his own grenade. I had seen him earlier in the aid station before his unit went and joined the attack, the attack had already begun, his unit was held back for a while then when he came into the aid station asking if we had anything for a cold. He had a cold and a headache and all the while he was in the aid station waiting to be treated he was eating, I remember so clearly because it affected me afterwards so much. He was eating chocolate powder out of a packet that you were supposed to mix with water to make a chocolate drink and he was just eating the powder and he got it kind of smeared on his face a little. And so finally I gave him the analgesic medicine for his cold and he went out and joined his unit and he was the one we found on the hill and that was another reason why that stayed with me so much. There are others that will come up. I find it difficult to just find something here because of tension, you understand. So…

We’ll go on to something else.

Company B, the whole combat command was ordered to take Herrlisheim, but only Company B went in at first, the other two companies, Company A and Company R, R for reserve, the reserve company – but they were often in the midst of the action too despite the reserve status, so they were standing by in case they were needed but since the enemy was only supposed to be Volkssturm they thought Company B could do it alone. And we established a forward aid station. Our captain, our medical captain liked this idea of having a rear aid station and a forward aid station. The forward aid station was much closer to the action and could treat the soldiers more quickly, and those who didn’t need immediate care could go back to the rear aid station. And at that time I was in the forward aid station. Company B had to attack over open land, exposed they were, it was a direct attack and could be seen by the enemy very easily, and also there was kind of an almost a parallel road that was built up a little bit and there were Germans on the other side of that parallel road watching the intervening land to pick off the Americans as they came across down that road, and they did that and Company B lost about in death or wounding over half of its men as they crossed this. My battalion, our combat command surgeon, whom with I became very friendly, Major Phibbs, told, he was familiar with the leaders of the combat command, he told them that in his opinion the attack should be made indirectly so they wouldn’t be openly exposed as they advanced but they said no, we are gong to take the quickest way and so they took the quickest way and for many it was the quickest way to death or injury.

How many men are in a company?

I think if my memory is correct, about 250 to a company in an armored division. I think in an infantry battalion, plain infantry battalion there are more to each company. Ours was made for quick, Germans had this too, they initiated it they called it . . .

Blitzkrieg?

Blitzkrieg, yeah, yeah exactly. And they used it to good advantage to tear through France and the Low Countries. So our troops, our men finally got in, those who survived, got into the northern part of Herrlisheim and were quickly attacked by German forces and they retreated into houses and fired from windows and doorways and so forth. And sometimes the Germans would come along and open the doors and fire into the Americans and they set fire to several of the houses, not all of them, so the Americans had to flee from the burning houses and expose themselves to a rain of gunfire and there were many, many casualties and finally the other companies, A and C, joined to offer support and they suffered fewer casualties because apparently the Germans had withdrawn their troops that were firing from the side and they got into the town too but they couldn’t hold the town, because there were too many Germans and too strong, they had tanks in the town. We couldn’t get our tanks into the town because the Germans had destroyed a bridge. The troops, when they left their halftracks and walked, they could jump over or wade through this small creak over which the destroyed bridge had spanned. And the engineers came in later and finally restored the bridge and then we could get at least the small, light tanks in to pick up the wounded and carry them out that way because the Germans would fire on an ambulance or anything else that tried. Some Germans would, not all of them. I encountered some decent Germans and there were some very bad Germans. Let me tell you about one of those SS guys and what he did. He was, he had concealed himself behind some huge rocks and he severely wounded one of the infantrymen in the sight of the two medics of his company, our two medics. One was a kind of a squat Italian fellow, very jolly sort of person and the other was a what do you call it when they are from Mexico?

Latino?

Latino, Latino, he was a wonderful guy and came from a difficult background, but he was great, both of them were great. And when they saw this man get shot and hear him yelling, screaming for help in terrible pain, the Spanish-American said I can’t stand it, I am going out there to help him in spite the gunfire from this SS guy and Pico, the other medic, tried to stop him from going, but he went anyway and he got to the wounded soldier and just bent down to try to help him and this SS guy opened up and just cut him in half and then he finished off the wounded soldier and Pico, his medic friend, co-medic, was so, so devastated by this because they were very good friends, that he had to come back to the station and somebody went out to replace him, for just a little while and I heard, I was, at that time I had received my promotion and was in that rear aid station where he came and he was just so upset, so upset talking about it and our captain was so upset too, and this, after the SS trooper had done his foul work an American group, a squad, came down behind him, down the draw behind him and saw him there and one of them threw a grenade at him and it landed at his feet, the SS man’s feet. The SS man saw it and he reached down to grab it and throw it back at the Americans but before he could throw it, it went off in his hand, and blew off his hand, and so he was brought to our aid station and he was treated and later on when, when our captain found out that he was the one who did it, he was just furious, but we still had to treat him and to evacuate him, that’s what we did. Finally Pico got over it and he went back out there to do his job. Those aid men, they had to face the same fire and danger that the infantrymen did, but when an infantryman was wounded they had to stay out there even if there was a barrage falling, to take care of them. And they did it, they were wonderful guys, I never had, well, except for that first time of barrage fall, they were wonderful guys, they did a lot of good work.

It turned out however that some of the SS were not that vicious. It’s wrong to say anything in a way that applies to the whole group, no matter what the group is, I found that even Republicans (laugh). So yes, but I would say that for the most part they were dedicated to devilish work. Our medical captain’s name was Captain Zimmerman and he’s quoted in the divisional history that I was able to get a copy of, he is quoted as reporting that the light tanks that were sent into Herrlisheim to bring out the wounded saved the lives of 65 soldiers. One of the tanks, one of the light tanks that went in was hit by a German shell and blown up and presumed that everybody in it was, including the tank personnel and the wounded that were on top were killed. One of our aid men, oh, when this Latino fellow was killed the captain asked for volunteers to replace him, he just couldn’t bring himself to say would you go out, you go out, and this medic who had been a graduate student at the University of Chicago, and who was writing a dissertation on detective fiction he volunteered—he was a strange school guy, very brilliant and very thick eyeglasses, why they let him in the army I have no idea! But he said “Oh I’ll go for heavens sake” and he went out, and he was wounded out there very quickly. He had a very bad compound fracture of the femur and so he was evacuated right away. Escaped further action but I don’t know how, whether he suffered permanent injury. So we got more medics then to replace those and a friend of mine from Army Specialized Training, from the college, his name was Johnny Kosinak grew up with a family in Connecticut, very nice fellow, very nice, very intelligent. He was an aid man with a company who attacked, which attacked and he was killed with that Company B that was crossing right in front of the eyes of these German soldiers who were hiding behind the railroad tracks, he was killed then too. So I lost two friends. And then for the troops that did get into Herrlisheim, nighttime was a nightmare for them because the Germans would come around and sometimes they would open a door and throw a grenade in and they would burn the houses as I mentioned before and they would shoot at the men if they tried to escape. And finally the light tanks, who were taking out the wounded began to take out the other men too, in other words we were getting out of Herrlisheim. There were just too many Germans there and many more than had been anticipated and much more firepower that they had. And the next day our men were asked to attack again. Straight on, they couldn’t get in so they came back, more wounded. And the next day they were sent in again, and they couldn’t get in. But I skipped over something, when the first batch came out there were so many of them that were either had what they called combat fatigue or were very close to it and they all were told to come to the rear aid station and to bed down there for the night and the chaplain who was with us, somehow I guess from the kitchen people, got a hold of a bunch of hamburger and buns, and he and some of the medics cooked up hamburgers and fed them to the wounded, to these soldiers who were just stressed out and they were laying on the floor covered with blankets and they enjoyed the hamburgers and slept there overnight. Unfortunately the next day they had to go back to their units. And yes, I had one of those hamburgers too, they were quite good (laugh). So finally it was decided that we, that an armored division was just not the sort of outfit to carry out this project successfully so they were replaced by a regular infantry division, in fact by two infantry divisions, one came in from either side to replace us as we pulled back out. And we went into a rather nice and rather long rest period. We had to get a lot of replacements for the men who had been killed or severely wounded and evacuated. When we were up to strength again we were ready for more action. And by then, the Rhine had been crossed and the Germans were beginning to pull back pretty fast so then we began to operate like a regular armored division. We raced through, we broke through the lines and continued on behind the German lines and then the regular infantry would come in behind us. We were on three separate highways, which were more or less parallel. Combat A was here, Combat Command A, Combat Command B and Combat Command R and we would just race as fast as we could and every now and then we would need to stop to overcome a German roadblock or something, but we always did it. This was our race through Germany. We went straight east for a while and then we turned and went south toward Austria. There are two things that I want to mention during this race. Of course at the front of the column there was always the possibility and the frequency of action but it was an action that was pretty quick. They got rid of the Germans pretty fast at that time. What a difference between that and Herrlisheim. We went through one town that looked like a nice peaceful town. There was this church with this nice, big slender tower and most of us had, most of the line of vehicles, what am I trying . . . ?

Convoy?

. . . convoy had gotten past this church and were further along in the little town and suddenly we heard a shot and everybody stopped and within a few minutes, every machine gun, .50 caliber and .30 caliber opened up on this church steeple and in the meantime a wounded soldier who had been hit by a sniper, he had been hit in the head and he was of course unconscious, and we retreated as best we could and we gave him some plasma and then he was taken away in an ambulance. I don’t know whether he survived or not, or if he survived how well he functioned. It’s very upsetting. So we all kind of became thrilled by the firepower that was directed at that steeple in which it was presumed the sniper was hiding and pretty soon that steeple was in flames and then it kind of fell down and there was no more firing from it of course and so our firing stopped and after a while we got settled down again and moved on. And the next thing that I especially remember is that we were coming down a draw that had been cut though a kind of little hill so that on each side of road was an embankment, and this led down to a main highway and we turned onto the highway and went down. Then I was riding in the ambulance with several other medics. The driver, I remember his name, his name was Merle Krisler, he was a wonderful guy, very young, but he had lost all of his teeth and he had a complete set of false teeth, but we got a message as we were going along that there were injuries in the draw and Merle, without hesitation, he was the driver, turned his ambulance around and I was sitting beside him and we went back to the draw and there was this halftrack stopped on the way down and we stopped just short of it and in front of the halftrack lay the driver of the halftrack, a tall man, also from ASTP as it turned out, and the others took a look at him and knew immediately that he was dead and they went on to find the other wounded who were up against an embankment so they were protected from one side, but not from the other. But I hesitated a moment, I wanted to be sure this guy was dead. Both of his feet had been blown off, and he was lying on the pavement in front of the halftrack, so I assumed that he had been blown right out of the seat, that the mortar shell had landed right at his feet and he had been thrown out. And when a person is dead, they no longer bleed because the heart isn’t pumping so his feet were missing and the stump of his leg was not bleeding so I knew that he was dead and that I could go on. And the other medics had already, there were only I think three others who were wounded, who were up against the embankment, and their wounds were not serious and they were taken care of and put into the ambulance and we took them back. But I don’t know where I was going with that…. Ah, we’ll just go on— so that was a very, I will never forget the sight of that man lying–oh I know what it was, many years later when I was working at the University of Chicago Press, they had a museum on campus and there was a– the museum had a courtyard and in that courtyard was a sculpture by Henry Moore and the sculpture was of a reclining figure whose legs, whose lower legs came to a point just the way that driver’s had come, and I remember being upset all over again. It may have been about this time that I decided that I wouldn’t make a good doctor (laugh) so I went into publishing instead. That, well we all almost got to Austria, we got to the border, a place called Bad Tolz, a little town, and we were told that the Germans ahead of us had surrendered. Part of our division did get into, a little bit into Austria but we didn’t, we didn’t get that far, but the Germans that we were facing surrendered and a day or two after that all of Germany surrendered and the war was over. So then we were so happy. And there is a picture that somebody took of a friend of mine who was a jeep driver for service company, service company, they weren’t combat people they were people who would take care of the vehicles and equipment, and he was a friend of mine, he was also from ASTP and he and I were sitting on the front of his jeep when somebody took our photograph and it was the day that victory had been announced and we were looking very happy. I noticed on it that I had a faint moustache; I had forgotten that I had tried to grow a moustache—it wasn’t very successful. So that was the end of our war. Then we were in occupation in a German town called Lauingen and while we were there I tried to take a swim in the Danube. I got down to my khaki briefs and plunged into the water and the current was so strong that I had no way of getting across so I just kind of drifted down with the water and tried to get over to, back to the side again and finally did after floating down maybe thirty or forty yards and I got out and that was the end of my swimming in the Danube. We were there for maybe a week or fortnight or something and then we were transferred to a town called Bopfingen and set up our dispensary there, it was no longer an aid station, it was a dispensary and the rest of the division were in adjacent cities, German cities, and while we were there Major Phibbs, my friend who was the combat command surgeon came to visit us several times and once when he came, a little German boy came in who had fallen and had a little gash in his head so Major Phibbs being there started to take care of him to debride the injury, to clean it up and sanitize it. And then when it was time to put the stitches in he said, “Go ahead John, put the stitches in” (laugh) so I did, I put the stitches in and I said “Is that alright?” And he said “Beautiful job”, so that was I think the beginning and the end of my career as a physician or something or physician-would-be. Or whatever.

Only operation

That’s right, so then I don’t know whether you heard of the point system. All of the soldiers received points for length of service or the number of engagements in which they were involved. Since I didn’t get into the army until ’43 and didn’t get overseas until late ’44 I didn’t have enough points to go home so they were going to send us, those who were with me, to the war against Japan. So we went up to a port near, a camp near Antwerp called Camp Top Hat and we were waiting in tents there for a ship that would take us to America where we would have a few days with our family and then go on to the war against Japan. They were ready to invade Japan. And while we were there we were listening to a radio, I don’t know where we got the radio, but there was a radio in our tent, and we heard that a new bomb, they called it an atomic bomb, was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, and I don’t know if they had mentioned the other one too, Nagasaki, but anyway they said Japan has capitulated and the war is over. Oh–it was a great relief (laughs), so then we went back into the army of occupation and I was sent to Vienna, to a dispensary in Vienna. It was great to be in Vienna, it was a wonderful place, went to the opera time and again with some friends and there was, we set up our dispensary, it was now a dispensary instead of an aid station. There was a young German lad who lived in the building and spoke very excellent English and he was a would-be poet and I was at that time, I was a would-be poet. We became friends and we shared each other’s poetry—I couldn’t understand his but he could understand mine because his was in German. And then he said he would take me, he wanted to take me to taste May wine, it was the time for May wine, and I had never had May wine and so I thought well, I’ll go along and taste it, and not being a seasoned drinker, I didn’t know when to stop! And this May wine just tasted so innocuous that I kept drinking it because it’s good, and the first thing you know I fell off the barstool! (laughing). I know, I know, it’s not the sort of thing I do! And so my friend, his name was Wagner, did I tell you that? His first name was Wagner, I can’t remember what his last name was, so he helped me up and said we better get back to (laughing) we better get home! So he took me, we walked for a while, I was able to walk I guess and we went to a subway station, and we were at the top of the stairs, and were ready to go down to get on the subway to go home, to the place were we had our dispensary and we lived, and I took a tumble down the stairs (laughing) all the way down! And it’s true, that the drunk are somehow protected because I didn’t really hurt myself! But I landed at the feet of a subway employee and he helped me up and Wagner spoke to him and said something in German and anyway this subway man turned out to be Wagner’s father (laughing), how come these things happen! (laughing). Anyway I got home and that was the end of my drinking (laughing), but he was a good guy, we had a good friendship. Then I went to, do I still have time? Then we had, Budapest was occupied by all the allies, the Russians had conquered Budapest but the occupation was shared with the allies, there was a British zone, there was an American zone and I think there may have been a French zone, I am not sure about the French zone, I am sure about the English and the American and the Russian. So we set up, I took the place of this guy who was going home, I can’t remember his name but he had more than sufficient points to go home, but he had stayed longer, he had chosen to stay longer and I couldn’t understand but I was told that he was engaged in some kind of black market activity and that he was making such good money that he couldn’t quite reconcile himself into going home. So he stayed and finally when I guess he had amassed his fortune he decided to go home. Although he told me, “I’m just going home for a furlough, I’ll be back!” you know as if it made any difference to me because I had to serve one place or another until I had sufficient points, so anyway he said he would be back but he never came back, of course. But I had such a wonderful time in Budapest. I met some wonderful people there. One of whom was a, belonged to a Russian aristocratic family. In Russia before the revolution there were so many aristocrats. Everybody above a certain level was a prince or this or that and he was a descendant of one of those families. His grandparents, I think it was, fled during the revolution. They were White Russians and the others, the communists were Red Russians. So they settled in Cincinnati, which oddly enough was my father’s birthplace. So I got to know him, he spoke perfect Russian of course and he spoke perfect British English, the accent was just marvelous and he was a great, we became close friends and made tours of Budapest. Budapest is originally two cities, Buda on the west side of the Danube and Pest is on the east of it. And they united sometime in the 18th century I think, or in the 19th, anyway somewhere they united to form the city of Budapest. We would often go over to the Pest side where the Imperial palace was, of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was in ruins at the time. We would drive around and I remember once doing it after a snowstorm and it was kind of a wet snow so that it packed up on top of walls and trees and it was just a gorgeous setting, really. Just beautiful and we would drive around. Then I went with other friends, I had different groups I became involved with, and this other group knew some girls who worked for the State Department over there, they had volunteered to work for the State Department and they lived in a little villa in Pest, no in Buda, and they invited us over and we had a little party there and one of the girls I think was Catholic because she gave me a copy of the poems of Charles Peguy who was a kind of liberal Catholic poet and I think she was a liberal Catholic too at the time. I took it and read it. I enjoyed the poetry and it was only much later that my slow mind realized that I think she was trying to convert me! (laughs) Well, I didn’t convert at that time anyway. But they were lovely girls (laughing) and we had a good time with them. So I had different groups that I went with and they were quite different but Sergei was a wonderful guy and I treasure his friendship. Finally I had accumulated sufficient points to come home, and to tell you the truth I was a little reluctant to leave Budapest because I was having such a good time but on the other hand I was eager to get home so we came home on a Henry J. Kaiser ship. I don’t know whether you heard of Henry J. Kaiser, for a while he made automobiles but I don’t think they lasted very long, competition against General Motors and Ford but he also made ships. He made them very quickly and they were slapped together and they worked for the most part. But we were on this ship coming home and it was a very rough sea! We had our own little section, I mean medics, all the medics who were aboard, they weren’t all from my outfit but they were from various outfits, they had a little section set up for us to have a dispensary there but the only illness that the guys, the soldiers going home on that boat suffered was seasickness. There was nothing we could do for them at the time and they left their coating of vomitus on the deck all over the ship! (laughs) Oh it was a very rough voyage and very hard on those who, I could, the bouncing up and down didn’t bother me but the sight of these poor boys, that was beginning to get to me. So finally the storms abated and we had a nice sunny day, one of the last days of our transatlantic voyage and we got out and somebody looked over the side of the ship at the prow and called everybody else’s attention to a big dent that had been made in the prow of the ship by the waves, and so we were glad that at least we hadn’t, that we weren’t at the bottom of the sea. We made it into harbor safely, we passed the Statue of Liberty, how nice it was to see that! And we landed in New York and I stopped to see my sister and her husband who were living in New York at the time. Then I went to a barber’s and had my haircut and had a shave. And then I went home and I arrived at the station in the basement of a tall, sort of, it was called Terminal Tower and it had a hotel attached to it and a business thing too and it was very high, at one time it was the highest structure in the world outside of New York City but it was only about fifty-two stories high so it has been surpassed many times. But I remember getting off the train, going to the stairs and coming up into the, I don’t know whether it was marble or granite or whatever, but from there leaning over the little wall were my parents and it was very nice to see them. I think they were glad to see me too. And so ended my military career. It was not as long as many boys had to go through, but it was enough to give me a taste of how ugly a thing war is. I thought, and many of us thought when the war ended that it would be peace from then on. And it was only two years later that the Korean War. When I was mustered out of the army they asked me “Would you like to join the reserves at your present rank” and I said no thank you, but those who did join ended up in Korea. So I made the right choice. So that’s my story, and I hope it serves your purposes.